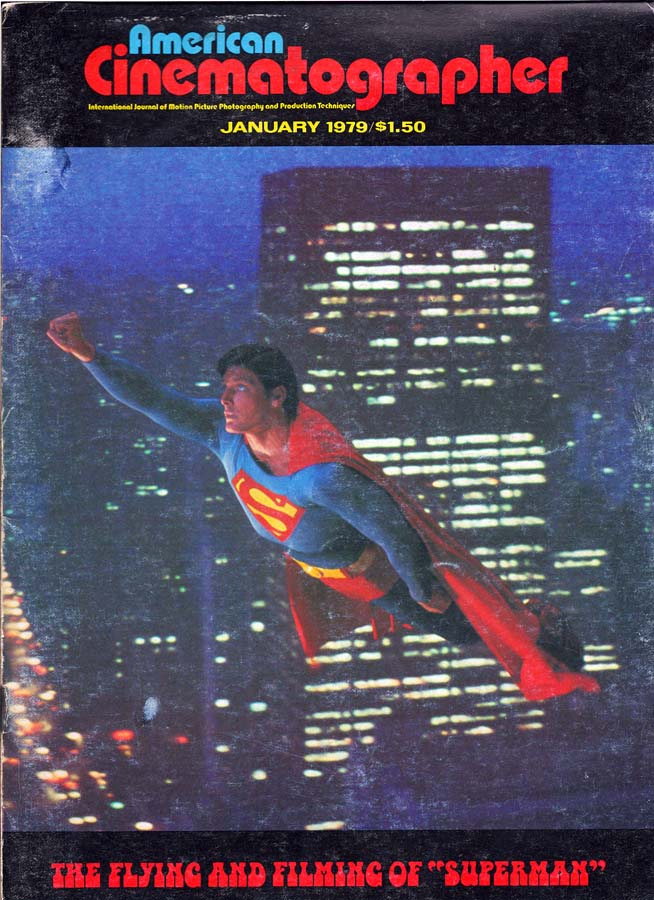

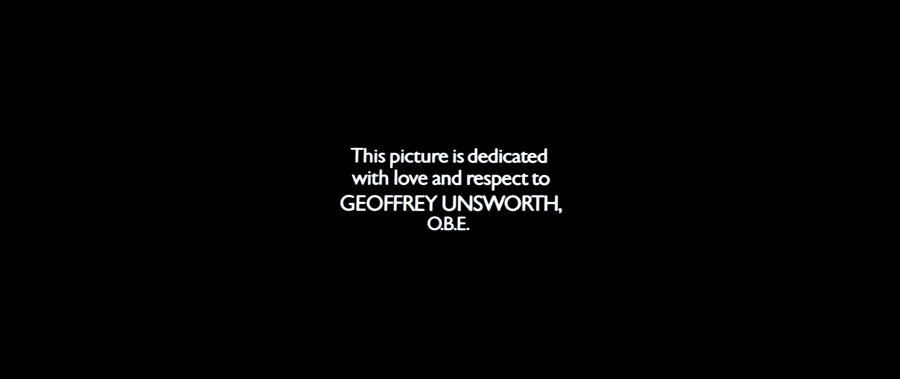

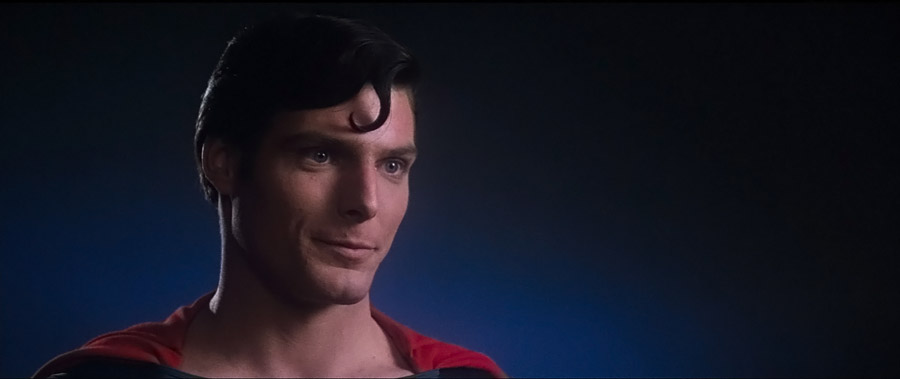

#5. After my sophomore year of high school, my family moved in the summer of 1978 to northern Virginia near Springfield. At the Air & Space Museum of the Smithsonian, I found a copy of “The Making of 2001” in the gift shop and spent the summer reading and re-reading it. I had few friends at my new school but one was a graphic artist and model builder; we made some science fiction short films in Super-8 and went to local science fiction conventions where I tried to sell some of my artwork. That Christmas, “Superman: The Movie” was released. At this point, I knew the names of two cinematographers, Vilmos Zsigmond and Geoffrey Unsworth (because of “2001”). After the lights dimmed and “Superman” began, the first title card was a dedication to Geoffrey Unsworth. I hadn’t realized he had passed away. I was also struck by the fact that he was awarded an O.B.E.; I didn’t know that a cinematographer could achieve such an honor. A few months later at a science fiction convention, I bought my first copy of American Cinematographer magazine, the issue about “Superman”. Peter MacDonald, his operator, wrote a lovely article about Unsworth’s work on that movie and his career in general. MacDonald had worked his way up from clapper-loader for Unsworth. What I recall the most was his description of the character of Unsworth, his professionalism, his calm demeanor. Over the years, I’ve read many positive comments about working with Unsworth from directors like Bob Fosse, Richard Attenborough, Roman Polanski, and John Boorman, plus a number of actresses who appreciated the care he took in lighting them.

My well-read issue:

The dedication at the head of the movie:

Unsworth is an interesting case of a studio-era cinematographer who, like Ozzie Morris, broke with tradition and started experimenting with diffusion, smoke, underexposure, and push-processing in an attempt to move away from the crisp Technicolor look of older movies. The soft, diffused, smokey look in color wasn’t new, it appeared in select moments when a certain dreamlike effect was desired in some Vincente Minnelli musical number, or the fog-filtered scenes in “Vertigo” or the dawn climax to “Black Narcissus.” But for an entire color movie, the only early precedent was Ozzie Morris’ work in “Moulin Rouge” (1952) using smoke and fog filters. By comparison, Unsworth’s work through the 1960’s like on “Beckett” was fairly clean (and of course there is “2001”). But by the start of the next decade, Unsworth was using smoke and diffusion on “Cabaret” (1972), just a year after Zsigmond’s work on “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” (1971). I was just reading something online about the studio execs of “Cabaret” complaining daily about the look – one of them claimed that he got Unsworth and Fosse to shoot some scenes clean “to the benefit of the movie”. I guess that exec also wants to take credit for the Oscar that Unsworth got for shooting the movie. (Reminds me of the old story about a studio exec yelling at Hitchcock in the 1940’s, saying something like “what in hell are you trying to do?” Hitchcock replied: “I’m attempting to make what you – in time – will call ‘our’ movie.”)

Like Vilmos Zsigmond and Ozzie Morris, Unsworth’s lighting was a mix of classic hard lighting from their training in b&w photography and modern soft-lighting techniques. In some ways, it straddles the transition from old-school studio photography and the more naturalistic work of the new generation of cinematographers to emerge in the 1970’s. Zsigmond of course is of that new generation, but with Zsigmond, you always sensed his love of classic studio lighting, which I would call “sculptural” in nature.

The wide shot of Jonathan Kent’s funeral in “Superman”, with the perfect white church in the background and puffy white clouds in the sky, is iconic in a sort of John Ford way. That shot was a touchstone for me when I shot “Northfork” in Montana. I loved reading in another publication that the church on the hilltop was a 1/4-scale false-front construction. Peter MacDonald mentioned that Unsworth had a high regard for Haskell Wexler and his work, and among British cinematographers, admired David Watkin for his photographic courage and in particular, his interior lighting on the movie “The Charge of the Light Brigade” (1968). He also mentioned that while on location, Unsworth would visit museums and art galleries on his days off. As a 16-year-old who studied art and painted on his spare time, I started to feel that my talents might be useful in filmmaking, either in cinematography or visual effects.

Copyright © CML. All rights reserved.

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- kino.png

- Hawk.png

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- Lowing.gif

- Module8Logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- lindseyo.jpg

- Aputure.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- VMI.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- FUJINON.jpg

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- FilmLightLogo.png

- theKeep.png

- NewLifeCineLogo.png

- PostWorks.png

- Aputure.png

- TCS.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- kino.png

- Hawk.png

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- Lowing.gif

- Module8Logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- lindseyo.jpg

- Aputure.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- VMI.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- FUJINON.jpg

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- FilmLightLogo.png

- theKeep.png

- NewLifeCineLogo.png

- PostWorks.png

- Aputure.png

- TCS.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- kino.png

- Hawk.png

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- Lowing.gif

- Module8Logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- lindseyo.jpg

- Aputure.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- VMI.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- FUJINON.jpg

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- FilmLightLogo.png

- theKeep.png

- NewLifeCineLogo.png

- PostWorks.png

- Aputure.png

- TCS.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- kino.png

- Hawk.png

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- Lowing.gif

- Module8Logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- lindseyo.jpg

- Aputure.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- VMI.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- aces.png

- 24-7.jpg

- 24-7.jpg

- arri.png

- arri.png

- BandH.jpg

- camalot.png

- camalot.png

- dedo.png

- dsc.png

- dsc.png

- FUJINON.jpg

- JustCinemaGear.jpg

- Leitz_logo.png

- Leitz_logo.png

- GodoxLogo.png

- Nanlux.png

- NPV_new_logo-(3)-(002).png

- NMBLogoForCML.png

- FilmLightLogo.png

- theKeep.png

- NewLifeCineLogo.png

- PostWorks.png

- Aputure.png

- TCS.png

- TC Logo Centered K_2.png

- zeiss-logo.png

- zeiss-logo.png